Funny Prison Conclusions Funny Prison Pictures

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

Drexel University researcher Sharrona Pearl was trying to track down stories of people changing their appearance to avoid law enforcement. She read about everything from train robbers from the 1960s, to folks escaping drug cartels, and, more recently, criminals trying to dodge facial recognition software.

"If you look into that, it turns out that you can uncover something else entirely," Pearl said.

She found record after record of plastic surgeries performed after criminals were caught and convicted: countless cosmetic procedures performed in prisons from the '60s through the late '80s.

"I was like, holy forking shirt balls!" Pearl recalled. Not exactly what she expected.

Initially, there was just a handful of decades-old newspaper articles.

"It actually was a little bit of digging, because there isn't a whole lot of secondary material written on this besides a couple of newspaper articles and one study done in the early nineties," Pearl said. "So it was really digging up out-of-print medical journals and tracking down criminology reports."

The basic idea was this: If you look better, people treat you better, and you'll have a better shot at staying out of prison. It was all about reducing recidivism.

Still, Pearl did find at least one record of a man whose surgery turned out a little too well: "There was one case in Canada … a petty thief and trickster [in] a kind of low-level sort of way. And then following his intervention, he became so handsome that he, upon release, was elevated into the life of a high-level confidence man and grifter."

There wasn't one big, coordinated plastic surgery push, one organization or university doing all this. The programs ran the gamut between highly structured partnerships between prisons and medical institutions and what were essentially handshake deals.

Usually, the surgeries were a kind of reward, a good behavior thing. Most of the patients were men, and most of them white. Prison populations were much smaller and much whiter during the decades before the war on drugs and before many mandatory sentencing minimums. Pearl said it seemed there was a greater focus on rehabilitation versus retribution.

For surgeons performing the surgeries, there was the feel-good side of helping with someone's rehabilitation, but also, especially for surgical students, there was a practical, personal benefit.

"So it was practice, it was practice on a vulnerable population. The students were not themselves given the option about whether or not to participate," Pearl said. "And certainly it was a cost-effective mechanism to be able to get training."

That's not to say there weren't plenty of seasoned pros — there was at least one surgeon to the stars operating on model prisoners in between operating on actual models.

"Harry Glassman. I mean, it was LA, the idea that you needed to look good to survive, perhaps made a lot of sense," Pearl said.

Operating on celebrities and the not-so-famous

Dr. Glassman is still practicing in Beverly Hills. You may have caught him on "Keeping up with the Kardashians," appearing in a season seven episode in which Kris Jenner sees him about cosmetic breast surgery.

"How did you dig up this story from God only knows how long ago?" he asked before our interview. I told him I didn't, that Pearl did.

As he remembers it, Glassman said, he only did about 40 operations, and his patients were all women. It started when he saw an article in the Los Angeles Times about how recidivism had reached about 70% in area corrections facilities. He was shocked it had gotten so high.

"So I just wondered whether helping people improve their appearance, or fix their scars, or remove their tattoos, or improve their self-esteem, whether those things would help somebody turn their life around and would change their recidivism rates," Glassman said.

He reached out to the LA County sheriff and proposed a kind of experiment: Glassman would perform surgeries free of charge on select women from the county jail, and the sheriff would track who stayed on the straight and narrow.

The sheriff agreed, on two conditions, Glassman said: "The first was that I was not permitted to operate on them while they were incarcerated. We agreed that the surgery would have to take place within two to three weeks after they were released from jail. And then the second stipulation was that we did not include in the group prostitutes, for fear that improving their appearance might only aid their prostitution. And that would skew the statistics on recidivism."

The jail didn't house the hardest of hardened criminals, it was mainly people convicted of minor robberies, assaults, frauds, forgeries, and, of course, prostitution. But no murderers or kidnappers. Glassman would visit once a month.

"They would post a questionnaire on the bulletin board, whether you were interested in seeing me," Glassman said. "And each time that I went there, there might be 60 or 80 different women who wanted to meet with me, and I'd meet with them for like five or 10 minutes apiece. And I would pick out two or three of them that I thought were really good candidates."

Being a good candidate meant having a combination of something Glassman thought was fixable — a scar or tattoo, a crooked nose, or protruding ears — and the person seeming as if she was serious about changing her ways.

Glassman told me about one person. He couldn't remember her real name, just what everyone called her: The Bird.

"There was something about this girl, she was the leader of one of the gangs in the jail, and her nose was horrible. I mean, her nickname was The Bird because of her nose," Glassman said. "She had a real attitude problem, but I kind of liked her so I didn't exclude her."

The Bird was selected for plastic surgery. A few weeks after her release, she went to Glassman's Beverly Hills office and sat among all the women who were paying full price. Even before the Kardashians, Glassman's operating room was familiar to the rich and famous.

"I don't treat anybody differently," he said. "The insecurities that very famous people and celebrities have are the same insecurities that non-celebrities have."

Glassman performed a rhinoplasty on The Bird — a nose job.

"It really changed her appearance in a very positive way. And of all of those, say, 40 that I operated on, I never heard from one of them afterwards, except this young woman stayed in contact with me for maybe 15 or 20 years," Glassman said.

She ended up turning her life around, starting a family, having kids. She was a success story, but she was maybe the only one.

"When the sheriff compiled all the statistics of these 40 some women, he reported back to me that within three years, the recidivism rate was 70%, which is exactly what it had been prior to my doing this," Glassman said.

Glassman had not moved the needle at all. He was disappointed, of course, and surprised too, but perhaps he shouldn't have been.

An earlier New York experiment

Before Glassman's program, there was at least one experimental surgery-versus-recidivism effort — at Sing Sing state correctional facility in New York, involving doctors from Montefiore Medical Center.

"And that one actually did have a federal grant behind it," Drexel researcher Pearl said. "And the people in the prison population who were accessing these services were divided into four groups."

The groups got a mix of vocational services and surgery or no intervention at all.

"If you look at the numbers, all the numbers, it seems to indicate that plastic surgery and vocational services is better than nothing at all, but surprisingly some of the groups of people who got vocational services and no plastic surgery actually did better from certain perspectives in terms of rates of recidivism," Pearl said. "And it depends how you slice and dice the data."

So the evidence in support of this kind of thing was never that robust, but Pearl said it was seen as a kind of obvious good. The surgeries, to Glassman and many of the doctors carrying them out, seemed altruistic.

"I think there's a real lack of cynicism and a lot of sincerity in these projects. And in my research, I look into the really challenging bioethical breaches that these experiments engage with," Pearl said. "But let me say that I think the people who were doing it genuinely believed that they were offering people the opportunity to better themselves, and perhaps that's not wrong."

Pearl noted that some of the prison plastic surgery proponents were also early proponents of gender affirming surgery, they were seen as kind of bleeding hearts in their day.

There is, though, the obvious ethical thorniness of essentially experimenting on a prison population, a group of less than "free" volunteers.

"It did seem to be desirable, but that's still wrapped up in a whole lot of coercion, right? If a guard says to you, `Here's something that I think you should do, because I think your looks are incredibly problematic,' is your desire to participate in that something that you want to do, something that you need to do?" Pearl said. "I think that these are really tricky questions when you're dealing with a vulnerable population who doesn't have a lot of freedom."

It's like nagging on steroids. Maybe you never even noticed your nose was a little crooked before a guard, a person who is in charge of huge parts of your day and life, told you it was kind of funny looking.

Yet the plastic surgeries went on for a long time, all across the country, and even in Canada and the U.K.

The Quasimodo Complex

"The British case is interesting because there the advocates were actually saying that on a sentencing board you should actually have a plastic surgeon," Pearl said. "And in fact, a plastic surgeon over a psychiatrist. And in fact, if you get plastic surgery as a young adult … in the juvenile system, that should count towards your sentence."

Appearance was tightly tied to crime during those years. I didn't know just how tightly until a criminologist on Reddit sent me an academic paper from the 1960s published in the British Journal of Plastic Surgery and titled, "The Quasimodo Complex."

Here's an excerpt:

"The entire field of psychosomatic medicine has developed around the concept that conflict can and does produce clinical symptoms. Frustration, tension, anxiety and emotional conflict may produce gastrointestinal ulceration. Relieve the anxiety, resolve the frustration, relax the tension, and the ulcerated mucous membrane may heal. These are well substantiated clinical facts that are widely accepted. The question is: Is the reverse true? Is it possible that physical abnormalities may produce emotional illness?"

The authors wrote about rising crime rates in the United States and wondered if correctable facial deformities were at least partially to blame.

They defined a handful of what they considered deformities: protruding ears, nose deformity, receding chin, scars, eye deformity, and a miscellaneous section. They looked for those markers in police mugshots from several city police departments, and from there they believed they found connections.

Suicide, which they and many states considered a crime at the time, correlated with nasal deformities, as did prostitution. Protruding ears were common among murders, and acne scars among rapists. They wrote about criminals they referred to as sex deviates:

"The sex deviate is emotionally disturbed, but the source of the disturbance is vague and often hidden behind a cloud of external symptoms. Evaluation of deformity in this group, both male and female, has shown an overall incidence of deformity of 56.9 per cent. with an unusually high percentage of protruding ears and receding chins … These two deformities can play an important part in the individual's development. The protruding ear is a source of jest from childhood, and the individual with a receding chin has been characterised as `weak and untrustworthy' by public prejudice."

Their survey found a 40% higher incidence of facial deformity among criminals. They closed by saying this wasn't conclusive proof, they couldn't say a crooked nose made a crook, but they did think their findings added a bit of evidence in support of that idea.

The idea that appearance and criminal behavior are related goes all the way back to the beginnings of the field of criminology.

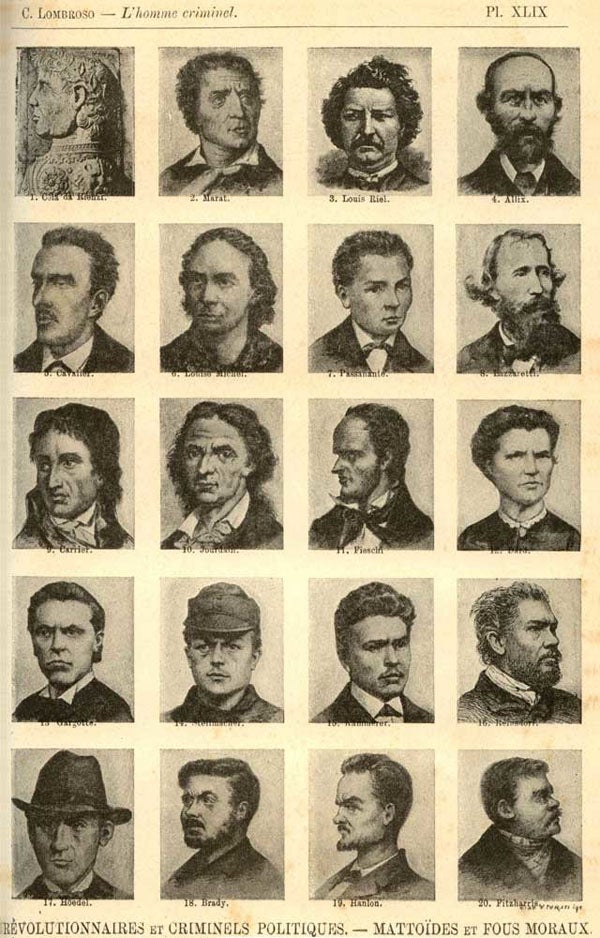

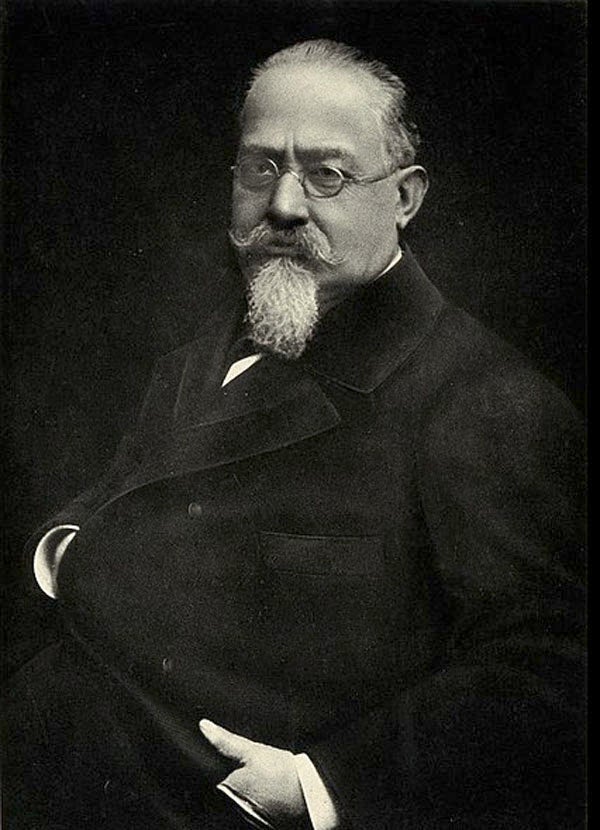

Kevin Thompson, a professor of criminal justice at North Dakota State University, said one of the first things covered in an introduction to criminology course is the idea that the discipline got its start with a physician named Cesare Lombroso in the 1870s.

"He began to uncover this idea that most of the inmates he was examining in prison populations were physically unattractive people. He actually referred to them as atavist, where they had missed the evolutionary line. And he felt that as a result of that, they were morally defective people," Thompson said.

Lombroso came up with terms like "criminaloid," what he considered a born criminal. He thought appearance was destiny.

Thompson found out about prison plastic surgery while it was still happening, in Texas in the late 1980s. He heard doctors from Baylor Medical Center were doing such surgeries, and after some poking around, found they were happening in at least 20 other states.

"We don't know how long this had been going on. My guess is, based on the data I was able to gather … for at least maybe 15 to 20 years before I started doing research on this topic," Thompson said. "So we have no idea, you know, how many inmates have had plastic surgery performed on them. It could be 4,000, it could be 80,000. We have no idea."

Modern privacy law, HIPAA, makes it incredibly hard to look into this now and retrieve those records. I told Thompson I'd make some calls, to hospitals, universities, prisons, to try and track some leads on former prisoners who went through this. He told me not to get my hopes up.

"Don't be surprised, Jad. If you run into roadblocks, you'll get probably, scurried from one person to another. This is not a topic that people feel comfortable talking about," he said. "But you can at least make some inquiries."

I did, a lot. Nothing. The closest I got was the plastic surgeon out in LA. It could be that it was just too long ago, or maybe people just don't want to talk about it. That's what Thompson thinks.

"It was too easy to do, put it that way. And for us to admit and go back and say, you know, this is what happened, you know, 40, 50, 60 years ago, this was a regular routine. A lot of people don't want to talk about that," he said.

Thompson thinks the efforts were well intentioned, but perhaps misguided. Most modern criminologists now think how people in prison looked was just the end result of much bigger, more complicated parts of their lives.

"It's kind of a triple whammy in some ways, that you combine genetics with this impoverished background. And then you end up in a lifestyle where you're involved in a lot of scuffles and fights and just kind of rough upbringing," Thompson said. "So all of that, I think, just adds up as these people go through life, and ultimately a significant minority of them end up in a prison population."

So what's more valuable than plastic surgery, more likely to keep someone out of prison than walking out of one with a new and improved face?

Thompson said it's simple; education, job opportunities, even joining a church. In short, a pathway back into society on the outside.

What brought the surgeons to this work?

So there was a lack of regulation, and a flawed link between appearance and crime at the heart of early criminology. That explains part of the story. But what attracted surgeons, plastic surgeons in particular, to performing these operations?

"Before you become a plastic surgeon … you have to go through general surgery," Glassman said. "So what are you seeing in general surgery? You're seeing people with cancer, gunshot wounds, stabbings, life-threatening illnesses. And so, during training, as a general surgeon, you save people's lives, you lose some people's lives. And then you go into plastic surgery. So, you know, when you've saved people's lives from cancer or, an auto accident, and then you start making people's noses smaller, you somehow, sometimes reflect on it in a very unusual sort of way."

Glassman said he knows cosmetic and reconstructive surgery makes huge differences in people's lives, but it's easy to forget that sometimes.

"I mean, personally, every once in a while, I struggle with being a plastic surgeon because I started thinking to myself, what am I really doing? " he said.

Maybe these surgeons wanted to feel more like the surgeons they used to be. They couldn't save lives, but they could preserve liberty. They could make what felt like a real difference, and they could do it in average people's lives, really in disadvantaged people's lives.

"I'd never been in a jail or prison before, or since, and I was touched by the humanity of it because some of them were just people that got caught up in the system, people who were desperate who forge checks in order to make it, get by," Glassman said. "Sort of like, `There but for the grace of God go I, you know,' they weren't horrible people. They just were, it sort of felt, I felt like they were victims of society."

Straightening a nose, pinning an ear, perhaps some doctors hoped that could fix something more wrong with society than with their patients.

Source: https://whyy.org/segments/unwrapping-the-strange-history-of-prison-plastic-surgery/

0 Response to "Funny Prison Conclusions Funny Prison Pictures"

Post a Comment