What Was Family Life Like for the Pilgrims

A painting by Robert W. Weir (1803–1890) showing Protestant pilgrims on the deck of the transport Speedwell before their departure for the New World from Delft Haven, Holland, on July 22, 1620. William Brewster, holding the Bible, and pastor John Robinson lead Governor Carver, William Bradford, Miles Standish, and their families in prayer. The prominence of women and children suggests the importance of the family unit in the customs. At the left side of the painting is a rainbow, which symbolizes hope and divine protection.

The Pilgrim Fathers is the mutual proper noun for a grouping of English separatists who fled an surround of religious intolerance in Protestant England during the reign of James I to establish the second English language colony in the New World. Dissimilar the colonists who settled Jamestown equally a commercial venture of the joint-stock Virginia Company in 1607, the Pilgrims migrated primarily to establish a community where they could practice their religion freely while maintaining their English identity.

Worshiping in various separatist churches in London, Norfolk and the Due east Midlands, the future pilgrims fled to religiously liberal Holland from 1593. Concerned with losing their cultural identity, the grouping arranged with English investors to establish a new colony in North America and made the dangerous Atlantic crossing on the Mayflower in 1620.

The founding of the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts and its historic charter, the Mayflower Compact, established early precedents for autonomous cocky dominion and the conventionalities that political and ceremonious rights were God-given. The Meaty promised "all due submission and obedience [to such] only and equal laws" that the fledgling customs might pass and, co-ordinate to Samuel Eliot Morrison, was "a startling revelation of the chapters of Englishmen in that era for self-government."[i]

The Plymouth colony's relations with Native Americans were largely peaceful, despite profound cultural misunderstandings. The devout Christian settlers non only won the sincere friendship of Indian leaders, they "set a model for interracial diplomacy that was followed, with varying success, by afterward Puritan colonies," according to New England colonial historian Alden Vaughn. "Justice, tolerance, decisiveness, and amity became the keystones of Plymouth's Indian policy." [2] Relations deteriorated with the passing of the showtime generation and the expansion of English settlement in New England, culminating in the regional Rex Phillip's War (1675), a watershed event that permanently altered the balance of power in favor of the numerically and technologically superior English colonists.

Contents

- i The origins of Separatism

- ane.1 Cambridge separatists

- 1.ii Nottinghamshire separatists

- 2 Migration to Holland

- 2.ane Leiden

- 2.2 Determination to leave

- 2.iii Negotiations

- ii.iv Brewster'due south diversion

- 2.5 Preparations

- three Voyage on the Mayflower

- 3.1 Arrival in America

- iii.2 Mayflower Compact

- iv Exploration and settlement

- 4.1 Contact

- 4.two Founding of Plymouth

- four.iii Growth and prosperity

- five The Pilgrims' legacy

- 6 Notes

- vii References

- 8 External links

- 9 Credits

The Pilgrims' epic voyage, perseverance amid burdensome hardships, and settlement in the New England wilderness, take come to be regarded as part of the narrative describing the birth of the United States. The Pilgrims' motivation of risking everything for the freedom to worship according to their conscience set a precedent that would come to be enshrined in the Outset Subpoena of the U.Due south. Constitution guaranteeing the free practice of religion.

The origins of Separatism

In 1586 a grouping of religious dissenters were sent to the Clink, the prison house in the London Borough of Southwark used for the detention of heretics, for refusing to obey the religious laws of the realm. Elizabeth I was trying to nautical chart a eye form between Roman Catholicism, which until recently had been the religion of England and was still close to the lives of her people, and the Reformed Church, which had broken with Rome during the reign of Elizabeth'south father, Henry VIII. The Elizabethan religious settlement had tried not to unnecessarily offend the Catholic sentiments of many Englishmen whose loyalty was necessary, while effectively restoring the Reformed Church after the interregnum of the Cosmic Queen ("Bloody") Mary.

English Puritans, influenced by the more than radical reform motion on the Continent, specifically by Calvinist doctrine, deplored the compromise and sought to cancel the episcopate, clerical vestments, and any authorized books of prayer. Radical Puritans went further, finding accommodation impossible and "separating" into unauthorized congregations to worship according to the dictates of conscience. Separatists were cruelly persecuted nether Mary, and enjoyed picayune tolerance under Elizabeth. The penalties for conducting "seditious" unofficial services included imprisonment, large fines, and execution. The London dissenters in the Clink however founded a church under the guidance of John Greenwood, a clergyman, and Henry Barrowe, a lawyer. They called themselves Independents, but were also known as Brownists because of the separatist ideas of Cambridge-educated Robert Browne.

Cambridge separatists

Cambridge University played an important part in advancing Puritan and separatist principles. Browne, Greenwood, Barrowe, and the future Pilgrim leader William Brewster were educated at Cambridge, as were other separatist leaders who would influence the theological, ecclesiastical, and political ideals of the Pilgrim Fathers. The atmosphere at Cambridge at this time was pro-Puritan and with a new spirit of reform. As a student Browne came under the influence of the Puritan theologian Professor Thomas Cartwright (1535-1603) and later on a period of instruction returned to Cambridge and preached sermons that burned with criticism of the established church. His brother had obtained licenses to preach for both of them, merely Robert had burnt his in protest. He came to pass up the Church building of England as unscriptural and also the Puritan view that the Church building could exist reformed from within. Browne set up up a Separatist congregation with his higher friend Robert Harrison in Norwich, but was imprisoned for unlicensed preaching afterward complaints from local priests.

While in Norwich Browne probably came into contact with Dutch Anabaptists who reinforced his telephone call for a new "truthful church ethic" that came to exist known as Congregationalism. Due to persecution Browne and Harrison moved most of the congregation to Zealand in Holland in 1582, where Cartwright had already established a Puritan congregation. In Holland Browne and Harrison wrote a number of works advocating reform of the Church of England. The books were presently banned and burned in England, and several members of the Norwich congregation were hanged for selling them. Browne later traveled around England and Scotland preaching dissident views for which he was imprisoned many times, but because of family unit connections he was soon released each fourth dimension. Browne ultimately reconciled with the established church, yet his writings were major contributions to the evolution of Elizabethan English religious dissent and the separatist movement. Many English dissidents would ready canvas for America and establish congregations forth the lines of basic Brownist theology, which is why Browne has frequently been called the father of Congregationalism.

View over Trinity Higher,Gonville and Caius College, and Clare Higher at Cambridge University

Similar Browne, Henry Barrowe (1550?-1593) studied at Cambridge under Thomas Cartwright, an good on the Acts of the Apostles and history of the early Church. Past profession a lawyer and from an old privileged family, Barrowe converted to strict Puritanism in 1580 after concluding that the Church of England had been tainted by Catholicism and was beyond any hope of redemption. Barrowe believed all their clergy and sacraments including infant baptism were invalid and rejected a church construction that placed layers of authority between the congregation and its ministers, as well as the apply of written public services such equally the Volume of Common Prayer. In its place he advocated a New Testament–oriented service "to reduce all things and actions to the true aboriginal and primitive pattern of God's Word."

With important implications for the Plymouth settlement and afterwards Congregational church construction in colonial America, Barrowe believed that truthful religion could merely exist in an ecclesiastical framework exterior the control of the country or any other external church building say-so. All authority was to be given to each congregation to govern themselves equally independent religious bodies. Ministers would not be appointed but elected by the membership of each individual congregation, and day-to-day management was delegated to its elected spiritual representatives: the pastor, elders, teachers, or deacons.

In 1587 members of an illegal congregation of John Greenwood (1554-1593), a graduate of Cambridge and ordained at Lincoln in 1582, were discovered and imprisoned in the Clink by order of the Archbishop of Canterbury John Whitgift. Barrowe, a friend of Greenwood and whose name was on the congregation list, was also arrested. While in prison Greenwood and Barrowe continued to write and their publications were smuggled out of England to be published in The netherlands. Barrowe was charged with seditious writing, and held in prison house. Meanwhile, in July 1592 Greenwood and other members were released on bail but to institute a new separatist church, with yet another Cambridge graduate, Francis Johnson (1562-1618), elected as its pastor. (From a respected Yorkshire family unit, Johnson had previously been commissioned to assist local English language authorities in Holland to buy and burn the books by Greenwood and Barrowe. Merely inspired by what he read, he embraced Barrowism and joining the church in Southwark in 1586.) However the reprieve was short-lived and in December Greenwood, Johnson, and others were again arrested. The church authorities examined Greenwood and Barrowe and sentenced them to death, and they were hung at Tyburn for sedition (a criminal offense against the authorities), not heresy.

The persecution of dissenters belied Elizabeth's expressions of moderation and famous affidavit that she didn't want to "brand windows into men'south souls." Only suppression of dissent, including harsh imprisonment and execution, can exist understood as a response to ceremonious unrest as much as to religious intolerance. The church building authorities seem to take been determined that the sentence would be carried out. However, four days later Queen Elizabeth I issued a statute assuasive for the adjournment of nonconformists instead of execution, although a third Cambridge separatist, John Penry (1563-1593), was executed in May.

In 1597 members of Johnson's congregation were released from prison and encouraged past the government to exit the country. Some joined the other Barrowists who had fled to Kingdom of the netherlands in 1593, while others were sent them to Canada to establish an English language colony on Rainea Island in the Saint Lawrence River. Four prominent Barrowist leaders gear up off on in April 1597, but ran into problems with French nationals and privateers and so eventually made their way to Holland to bring together the rest of the congregation.

Nottinghamshire separatists

Another pregnant group of people who would formed the nucleus of the future Pilgrims were brought together through the teachings of Richard Clyfton, parson at All Saints' Parish Church in Babworth, Nottinghamshire, between 1586 and 1605. This congregation held Separatist beliefs similar to the nonconforming movements led by Barrowe and Browne. William Brewster, a former diplomatic assistant to the Netherlands, was living in the Scrooby manor house and serving as postmaster for the village and bailiff to the Archbishop of York. Brewster may accept met the teenage William Bradford from nearby Austerfield on the so-chosen Pilgrim Way, a still-extant trail that led to the Babworth church. Orphaned and with fiddling formal educational activity, Bradford would later serve equally governor of Plymouth Colony for nearly twoscore years, author the historical chronicle Of Plimoth Plantation (the most of import master source of the Plymouth colony), and be remembered equally the leading figure in seventeenth-century colonial American history.

Having been favorably impressed past Clyfton's services, Brewster and Bradford began participating in Separatist services led by John Smyth, a Barrowist and friend of Johnson, in unincorporated (and thus largely unmonitored) Gainsborough, Lincolnshire.[3]The lord of the ancient manor house, William Hickman, was an ardent Protestant whose family had survived the religious persecutions of Henry Viii. Sympathetic to the separatists, Hickman offered his protection and hosted the secret meetings.

The All Saints Parish Church in Babworth, where William Bradford and William Brewster heard the separatist sermons of Richard Clyfton.

During much of Brewster's tenure (1595-1606), the Archbishop of Canterbury was Matthew Hutton. He displayed some sympathy for the Puritan cause, writing in 1604 to Robert Cecil, a relative of Robert Browne and secretarial assistant of state to James I:

The Puritans (whose phantasticall zeale I mislike) though they differ in Ceremonies & accidentes, still they agree wth us in substance of religion, & I thinke all or the moste p[ar]te of them love his Ma[jes]tie, & the p[re]sente state, & I hope will yield to conformitie. But the Papistes are opposite & contrarie in very many substantiall pointes of religion, & cannot but wishe the Popes authoritie & popish religion to be established.[4]

It had been hoped that when James came to power, a reconciliation allowing independence would be possible, only the Hampton Court Conference of 1604 denied substantially all the concessions requested by Puritans, salvage for an English language translation of the Bible. To the demand to abolish the episcopate James responded, "No Bishop, no King." Reform along Puritan lines could have unravelled the whole political organisation causing more instability at a time of standing foreign threats. These of import issues resurfaced later resulting in the English language Civil War. Following the Conference, in 1605 Clyfton was declared a nonconformist and stripped of his position at Babworth. Brewster invited Clyfton to live at his dwelling house.

Upon Hutton'due south 1606 death, Tobias Matthew was elected as his replacement. Matthew, i of James' principal supporters at the 1604 briefing, promptly began a campaign to purge the archdiocese of nonconforming influences, both separatists and papists. Disobedient clergy were replaced, and prominent Separatists were confronted, fined, imprisoned, or driven out of the land.[5]

At about the same time, Brewster arranged for a congregation to meet privately at the Scrooby manor house. Beginning in 1606, services were held with Clyfton as pastor, John Robinson a graduate of Corpus Christi, Cambridge, as instructor, and Brewster as the presiding elder. Shortly thereafter, Smyth and members of the Gainsborough group moved on to Holland, first joining Johnson's congregation and afterwards establishing his own congregation in Amsterdam in 1608.

In September 1607 Brewster resigned from his postmaster position and according to records was fined £20 (2005 equivalent: about £2000) in absentia for his noncompliance with the church.[vi] Facing increasing harassment, the Scrooby congregation decided shortly after to follow the Smyth party to Amsterdam. Scrooby member William Bradford of Austerfield kept a periodical of the congregation'south events that would later be published as Of Plymouth Plantation. Of this time, he wrote:

Merely after these things they could non long continue in whatsoever peaceable condition, only were hunted & persecuted on every side, so as their onetime afflictions were simply as flea-bitings in comparing of these which now came upon them. For some were taken & clapt up in prison house, others had their houses besett & watcht dark and twenty-four hours, & hardly escaped their hands; and ye most were faine to flie & get out their howses & habitations, and the means of their livelehood.[7]

Migration to Holland

Unable to obtain the papers necessary to leave England, members of the congregation agreed to get out surreptitiously, resorting to bribery to obtain passage. I documented endeavour was in 1607, post-obit Brewster's resignation, when members of the congregation chartered a boat in Boston, Lincolnshire. This turned out to be a sting operation, with all arrested upon boarding. The entire party was jailed for one month awaiting arraignment, at which time all but seven were released. Missing from the record is for how long the remainder was held, just it is known that the leaders made it to Amsterdam near a year subsequently.

In a second difference effort in the spring of 1608, arrangements were fabricated with a Dutch merchant to pick up church members forth the Humber estuary at Immingham almost Grimsby, Lincolnshire. The men had boarded the ship, at which time the sailors spotted an armed contingent approaching. The send quickly departed before the women and children could board; the stranded members were rounded upwards just then released without charges.

Ultimately, at to the lowest degree 150 of the congregation did make their style to Amsterdam, meeting upward with the Smyth political party, who had joined with the Exiled English Church building led past Francis Johnson (1562-1617), Barrowe'due south successor. The atmosphere was difficult considering of the growing tensions between Smyth and Johnson. Smyth had embraced the idea of believer's baptism, which Clyfton and Johnson opposed. [8]

Robinson decided that it would exist best to remove his congregation from the fray, and permission to settle in Leiden was secured in 1609. With the congregation reconstituted as the English Exiled Church in Leyden, Robinson now became pastor while Clyfton, advanced in age, chose to stay behind in Amsterdam.

Leiden

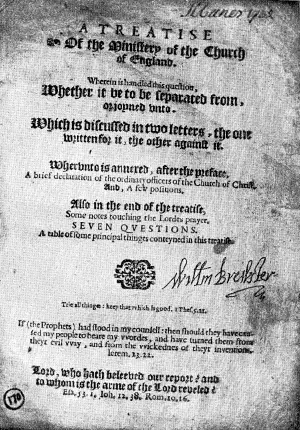

Championship page of a pamphlet published past William Brewster in Leiden

The success of the congregation in Leiden was mixed. Leiden was a thriving industrial center, and many members were well able to support themselves working at Leiden University or in the textile, printing and brewing trades. Others were less able to bring in sufficient income, hampered by their rural backgrounds and the language barrier; for those, accommodations were fabricated on an estate bought by Robinson and 3 partners.[9]

Of their years in Leiden, Bradford wrote:

For these & another reasons they removed to Leyden, a off-white & bewtifull citie, and of a sweete state of affairs, but made more famous by ye universitie wherwith it is adorned, in which of late had been so many learned human. But wanting that traffike past ocean which Amerstdam injoyes, it was non and so beneficiall for their outward means of living & estats. But beingness at present hear pitchet they fell to such trads & imployments as they best could; valewing peace & their spirituall comforte above any other riches whatsoever. And at length they came to enhance a competente & comforteable living, but with difficult and continuall labor.

Brewster had been teaching English at the university, and in 1615, Robinson enrolled to pursue his doctorate. There, he participated in a series of debates, particularly regarding the contentious issue of Calvinism versus Arminianism (siding with the Calvinists confronting the Remonstrants). Brewster, in a venture financed by Thomas Brewer, acquired typesetting equipment well-nigh 1616 and began publishing the debates through a local printing.[10]

Holland was, however, a land whose culture and language were foreign and difficult for the English language congregation to empathize or learn. Their children were becoming more and more Dutch equally the years passed by. The congregation came to believe that they faced eventual extinction if they remained in Holland. They wanted to either return to England or move as costless Englishmen to a new English homeland beyond the sea.

Decision to leave

By 1617, although the congregation was stable and relatively secure, at that place were ongoing issues that needed to exist resolved. Bradford noted that the congregation was aging, compounding the difficulties some had in supporting themselves. Some, having spent their savings, gave upwardly and returned to England. It was feared that more would follow and that the congregation would become unsustainable. The employment issues made it unattractive for others to come up to Leiden, and younger members had begun leaving to find employment and adventure elsewhere. As well compelling was the possibility of missionary work, an opportunity that rarely arose in a Protestant stronghold.[xi]

Reasons for deviation are suggested past Bradford, when he notes the "discouragements" of the hard life they had in The netherlands, and the promise of alluring others by finding "a better, and easier place of living"; the "children" of the group being "drawn away by evil examples into extravagance and dangerous courses"; the "great hope, for the propagating and advancing the gospel of the kingdom of Christ in those remote parts of the world."

Pilgrim Edward Winslow'southward recollections support Bradford's account: In addition to the economic worries and missionary possibilities, Winslow stressed that information technology was important for the people to retain their English identity, culture and language. They also believed that the English Church building in Leiden could practice little to benefit the larger community there.[12]

At the same time, there were many uncertainties most moving to such a place equally America. Stories had come back about the failed Sagadahoc colony in today's Maine and of the hardships faced by the Jamestown settlement in Virginia. There were fears that the native people would be violent, that at that place would be no source of food or water, that exposure to unknown diseases was possible, and that travel by bounding main was e'er hazardous. Balancing all this was a local political situation that was in danger of becoming unstable: the truce in what would be known as the Eighty Years' War was faltering, and there was fear over what the attitudes of Espana toward them might be.

Possible destinations included Guiana, where the Dutch had already established Essequibo; or somewhere near the existing Virginia settlement. Virginia was an attractive destination because the presence of the older colony might offer better security. Information technology was thought, however, that they should not settle also nearly and thus fall into the same restrictive political environment every bit in England.

Negotiations

The congregation decided to petition the English Crown for a lease to establish an English colony in the New Globe. Some were concerned nigh approaching the government of King James that had forced them into exile. Nonetheless William Brewster had maintained the contacts he had developed during his period of service with William Davison, sometime Secretarial assistant of State under Queen Elizabeth. John Carver and Robert Cushman were dispatched to London to human action as agents on behalf of the congregation. Their negotiations were delayed considering of conflicts internal to the London Visitor, simply somewhen a patent was secured in the name of John Wincob on June 9, 1619.[13] The charter was granted with the rex's condition that the Leiden group's religion would not receive official recognition.[14]

Because of the connected problems within the London Company, preparations stalled. The congregation was approached by competing Dutch companies, and the possibility of settling in the Hudson River area was discussed with them. These negotiations were broken off at the encouragement of another English merchant, Thomas Weston, who assured the anxious group that he could resolve the London Company delays.[15]

Weston did come up back with a substantial change, telling the Leiden group that parties in England had obtained a land grant north of the existing Virginia territory, to be called New England. This was only partially truthful; the new grant would come to laissez passer, but not until late in 1620 when the Plymouth Quango for New England received its charter. Information technology was expected that this area could be fished profitably, and it was not under the control of the existing Virginia government.[16]

A second change was known merely to parties in England who chose not to inform the larger grouping. New investors who had been brought into the venture wanted the terms contradistinct so that at the terminate of the seven-year contract, half of the settled land and property would revert to them; and that the provision for each settler to have two days per week to work on personal business was dropped.

Brewster's diversion

Amid these negotiations, William Brewster found himself involved with religious unrest emerging in Scotland. In 1618, James had promulgated the V Articles of Perth, which were seen in Scotland as an attempt to encroach on their Presbyterian tradition. Pamphlets disquisitional of this law were published by Brewster and smuggled into Scotland past April 1619. These pamphlets were traced back to Leiden, and a failed attempt to apprehend Brewster was made in July when his presence in England became known.

Also in July in Leiden, English administrator Dudley Carleton became aware of the situation and began leaning on the Dutch government to extradite Brewster. Brewster's blazon was seized, simply only the financier Thomas Brewer was in custody. Brewster'south whereabouts between then and the colonists' departure remain unknown. Later several months of delay, Brewer was sent to England for questioning, where he stonewalled government officials until well into 1620. I resulting concession that England did obtain from the Netherlands was a restriction on the press that would make such publications illegal to produce. Brewster was ultimately bedevilled in England in absentia for his continued religious publication activities and sentenced in 1626 to a 14-twelvemonth prison house term.[17]

Preparations

As many members were not be able to settle their affairs within the fourth dimension constraints and the budget for travel and supplies was limited, it was decided that the initial settlement should be undertaken primarily by younger and stronger members. Accordingly, the decision was made for Robinson to remain in Leiden with the larger portion of the congregation, and Brewster to atomic number 82 the American congregation. While the church building in America would be run independently, information technology was agreed that membership would automatically be granted in either congregation to members who moved betwixt the continents.

With personal and concern matters agreed upon, supplies and a small ship were procured. The Speedwell was to bring some passengers from the Netherlands to England, then on to America where the ship would exist kept for the angling business, with a coiffure hired for back up services during the commencement yr. A second, larger send, the Mayflower, was leased for transport and exploration services.[18]

Voyage on the Mayflower

In July 1620 i hundred and 20 members of the Leyden Barrowist congregation under the spiritual leadership of William Brewster as Elder departed Delfshaven in the Speedwell for Plymouth. There they met the London Company representatives, and their sister ship the Mayflower that would transport the employees of the London Visitor to found their trading mail service. When they arrived in Plymouth the Barrowists were welcomed by the local church building. Yet before the ships prepare sail a number of disagreements occurred between the representatives of the London Company and the Leiden colonists. Some of the London Company representatives tried to make a profit off the colonists in Plymouth and many of the colonists had disagreements with the London Company employees on the Mayflower.

The Mayflower and the Speedwell prepare sail from Plymouth on August 5, 1620. After a week problems developed on the Speedwell and they had to return to Dartmouth Harbor. Afterwards repairs they set sail again for America. Inside a few days they had to render to Plymouth for boosted repairs to the Speedwell. Information technology was decided to abandon the Speedwell and put everyone on the London Company'south ship the Mayflower. Of the 120 Speedwell passengers, 102 were chosen to travel on Mayflower with the supplies consolidated. The Mayflower set sail from Plymouth on September sixteen, 1620.

Initially the trip went smoothly, but under way they were met with strong winds and storms. I of these caused a main beam to crack, and although they were more than than half the way to their destination, the possibility of turning back was considered. Using a "great atomic number 26 spiral" they repaired the transport sufficiently to continue. I rider, John Howland, was done overboard in the storm simply defenseless a rope and was rescued. 1 crew fellow member and one passenger died earlier they reached land, and 1 child was born at sea, and named "Oceanus."[19]

Arrival in America

State was sighted on November 20, 1620. Information technology was confirmed that the area was Cape Cod, within the New England territory recommended by Weston. An attempt was made to canvass the ship around the greatcoat towards the Hudson River, as well within the New England grant expanse, but they encountered shoals and difficult currents around Malabar (a land mass that formerly existed in the vicinity of present-day Monomoy). It was decided to turn effectually, and by November 21 the ship was anchored in what is today known as Provincetown Harbor.

Mayflower Compact

This bas-relief depicting the signing of the Mayflower Meaty is on Bradford Street in Provincetown directly below the Pilgrim Monument.

With the charter for the Plymouth Council for New England incomplete by the time the colonists departed England (information technology would be granted while they were in transit, on November thirteen), the Pilgrims arrived without a patent. Some of the passengers, aware of the state of affairs, suggested that without a patent in place, they were free to practise every bit they chose upon landing and ignore the contract with the investors.[20]

To address this upshot and in response to sure "mutinous speeches," a brief contract, signed on November eleven, 1620 on board the Mayflower, after to be known as the Mayflower Meaty, was drafted promising cooperation among the settlers "for the general skillful of the Colony unto which nosotros promise all due submission and obedience." The certificate was ratified past majority dominion, with 41 adult male passengers signing.[21]

The original certificate has been lost, but Bradford'south transcription is as follows:

In the name of God, Amen. We whose names are underwritten, the loyal subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord Rex James, by the Grace of God of Smashing Britain, France and Ireland, Male monarch, Defender of the Faith, etc. Having undertaken, for the Glory of God and advancement of the Christian Faith and Laurels of our King and State, a Voyage to plant the First Colony in the Northern Parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God and i of another, Covenant and Combine ourselves together into a Ceremonious Body Politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute and frame such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions and Offices, from time to time, as shall exist thought about meet and user-friendly for the general good of the Colony, unto which we hope all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Greatcoat Cod, the 11th of November, in the year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, French republic and Ireland the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth. Anno Domini 1620.

At this time, John Carver was chosen as the colony'south get-go governor.

Exploration and settlement

Thorough exploration of the area were delayed for over two weeks because the shallop or pinnace (a smaller sailing vessel) they brought had been partially dismantled to fit aboard Mayflower and was further damaged in transit. Pocket-size parties did wade to the beach to fetch firewood and attend to long-deferred personal hygiene.

While awaiting the shallop, exploratory parties led by Myles Standish—an English soldier the colonists had met while in Leiden—and Christopher Jones were undertaken. They encountered several quondam buildings, both European- and Native-congenital, and a few recently cultivated fields.

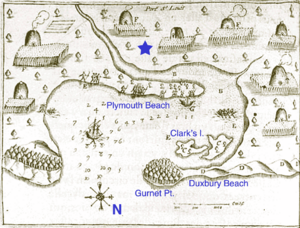

1620 places of importance mentioned by William Bradford

An artificial mound was found near the dunes, which they partially uncovered and found to be a Native grave. Further forth, a similar mound, more recently made, was found, and as the colonists feared they might otherwise starve, they ventured to remove some of the provisions which had been placed in the grave. Baskets of maize were plant inside, some of which the colonists took and placed into an iron kettle they also plant nearby, while they reburied the rest, intending to use the borrowed corn equally seed for planting.

Bradford after recorded that after the shallop had been repaired,

They likewise found two of the Indian'due south houses covered with mats, and some of their implements in them; just the people had run away and could non be seen. They also found more corn, and beans of various colours. These they brought away, intending to give them full satisfaction (repayment) when they should meet with any of them, – as nearly six months afterward they did.

And information technology is to be noted as a special providence of God, and a great mercy to this poor people, that they thus got seed to establish corn the side by side year, or they might have starved; for they had none, nor whatever likelihood of getting any, till too late for the planting flavour.

By December, nearly of the passengers and crew had go sick, coughing violently. Many were also suffering from the effects of scurvy. In that location had already been ice and snowfall, hampering exploration efforts.

Contact

Explorations resumed on Dec sixteen. The shallop political party—vii colonists from Leiden, three from London, and vii crew—headed down the greatcoat and chose to land at the area inhabited by the Nauset people (roughly, present-24-hour interval Brewster, Chatham, Eastham, Harwich, and Orleans, Massachusetts) where they saw some native people on the shore, who ran when the colonists approached. Inland they institute more mounds, one containing acorns, which they exhumed and left, and more than graves, which they decided not to dig.

Remaining ashore overnight, they heard cries near the encampment. The following morning, they were met past native people who proceeded to shoot at them with arrows. The colonists retrieved their firearms and shot back, then chased the native people into the woods simply did non find them. There was no more contact with native people for several months.

The local people were already familiar with the English language, who had intermittently visited the area for fishing and trade earlier Mayflower arrived. In the Cape Cod area, relations were poor following a visit several years before by Thomas Chase. Hunt kidnapped 20 people from Patuxet (the place that would become New Plymouth) and another seven from Nausett, and he attempted to sell them as slaves in Europe. One of the Patuxet abductees was Squanto, who would get an ally of the Plymouth colony. The Pokanoket, who besides lived nearby, had developed a item dislike for the English after one grouping came in, captured numerous people, and shot them aboard their ship. At that place had by this fourth dimension already been reciprocal killings at Martha's Vineyard and Greatcoat Cod.

Samuel de Champlain's 1605 map of Plymouth Harbor, showing Wampanoag village Patuxet, with some modern place names added for reference. The star is the gauge location of the 1620 English language settlement.

Founding of Plymouth

Standing w, the shallop's mast and rudder were cleaved by storms, and their sail was lost. Rowing for safety, they encountered the harbor formed by the current Duxbury and Plymouth barrier beaches and stumbled on land in the darkness. They remained at this spot—Clark'southward Island—for two days to recuperate and repair equipment.

Resuming exploration on December 21, the party crossed over to the mainland and surveyed the area that ultimately became the settlement. The anniversary of this survey is observed in Massachusetts as Forefathers' Day and is traditionally associated with the Plymouth Rock landing fable. This country was especially suited to wintertime building because the country had already been cleared, and the tall hills provided a good defensive position.

The cleared hamlet, known as Patuxet to the Wampanoag people, was abandoned nearly three years earlier following a plague that killed all of its residents. Because the affliction involved hemorrhaging, the "Indian fever" is assumed to accept been fulminating smallpox introduced past European traders. The outbreak had been astringent enough that the colonists discovered unburied skeletons in abandoned dwellings.[22] With the local population in such a weakened state, the colonists faced no resistance to settling at that place.

The exploratory political party returned to the Mayflower, which was then brought to the harbor on December 26. Only nearby sites were evaluated, with a loma in Plymouth (so named on earlier charts) chosen on December 29.[23]

Construction commenced immediately, with the beginning mutual house nearly completed by January 19. At this signal, unmarried men were ordered to bring together with families. Each extended family unit was assigned a plot and built its own habitation. Supplies were brought ashore, and the settlement was generally complete past early February.

Between the landing and March, only 47 colonists had survived the diseases they contracted on the ship. During the worst of the sickness, only half dozen or 7 of the group were able and willing to feed and care for the rest. In this time, half the Mayflower coiffure also died.

On March xvi, 1621, the colonists were surprised when an Indian boldly entered the Plymouth settlement and greeted them in English. Samoset was a sagamore (subordinate primary) of an Abenaki tribe from Pemaquid, Maine, and had learned some English from the English language fishermen that frequented Maine's coastal waters. Later on spending the night with the Pilgrims, he returned two days later with Squanto, who spoke English language much ameliorate than Samoset and arranged for the Pilgrims to meet with the chief sachem of the Wampanoag, Massasoit.

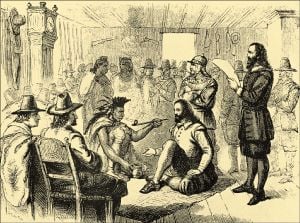

On March 22, 1621, the Pilgrims signed a peace treaty with Massasoit guaranteeing the English their security in commutation for their alliance against the Narragansett. Massasoit held the allegiance of 7 lesser Wampanoag sachems and actively sought the alliance since ii significant outbreaks of smallpox brought past the English had devastated the Wampanoag during the previous six years.

William Bradford became governor in 1621 upon the death of Carver and served for 11 consecutive years. (He was elected to various other terms until his death in 1657.) Subsequently their first harvest in 1621, Bradford invited Massasoit and the Wampanoag people to join in a feast of thanksgiving. Edward Winslow provided an business relationship of this nearly-mythical first Thanksgiving in his diary:

Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent 4 men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruits of our labor. They iv in one twenty-four hour period killed as much fowl as, with a piffling help abreast, served the company well-nigh a week. At which fourth dimension, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amid the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for 3 days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which we brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain and others. And although it be not always then plentiful as it was at this time with u.s., nonetheless by the goodness of God, we are then far from want that we frequently wish y'all partakers of our enough.

An annual Thanksgiving after harvest became traditional in the seventeenth century. George Washington created the beginning Thanksgiving 24-hour interval designated by the national government of the Us on October three, 1789. The modern Thanksgiving holiday is often credited to Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of Boston's Ladies' Mag. Commencement in 1827, she wrote editorials calling for a national, almanac day of thanksgiving to commemorate the Pilgrim's first harvest feast. Afterward about 40 years, in 1863, Abraham Lincoln alleged the first modern Thanksgiving to fall on the last Thursday in Nov. President Franklin Roosevelt and Congress ultimately moved information technology to the fourth Thursday in November, and in 1941, the holiday was recognized by Congress as an official federal holiday.[24]

Growth and prosperity

Massasoit smoking a peace pipe with Governor John Carver in Plymouth 1621.

Co-ordinate to Bradford and other sources, Massasoit prevented the failure of Plymouth Colony and the nearly certain starvation that the Pilgrims faced during the earliest years of the colony's establishment. Moreover, Massasoit forged disquisitional political and personal ties with the colonial leaders John Carver, Stephen Hopkins , Edward Winslow, William Bradford, and Myles Standish. Massasoit's alliance ensured that the Wampanoag remained neutral during the Pequot War in 1636. Winslow maintained that Massasoit held a deep friendship and trust with the English and felt duty-bound to observe that "whilst I live I will never forget this kindness they have showed me." [25] Unfortunately, the peaceful human relationship that Massasoit had worked and so diligently to create and protect had unforeseen dire consequences for the Wampanoag.

In November 1621, 1 year later the Pilgrims first set foot in New England, a second ship sent by the Merchant Adventurers arrived. Named the Fortune, it arrived with 37 new settlers for Plymouth. However, as the send had arrived unexpectedly, and too without many supplies, the additional settlers put a strain on the resources of the colony. Among the passengers of the Fortune were several additional members of the original Leiden congregation, including William Brewster'southward son Jonathan, Edward Winslow'due south brother John, and Philip de la Noye (the family name was later changed to "Delano") whose descendants include President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Fortune also carried a alphabetic character from the Merchant Adventurers chastising the colony for failure to return goods with the Mayflower that had been promised in return for their support. The Fortune began its render to England laden with ₤500 worth of goods, more than than enough to keep the colonists on schedule for repayment of their debt, however the Fortune was captured past the French earlier she could deliver her cargo to England, creating an even larger deficit for the colony.[26]

In July 1623, two more than ships arrived, carrying 90 new settlers, among them Leideners, including William Bradford'southward time to come wife, Alice. Some of the settlers were unprepared for borderland life and returned to England the next year. In September 1623, another ship carrying settlers destined to refound the failed colony at Weymouth arrived and temporarily stayed at Plymouth. In March 1624, a ship begetting a few additional settlers and the first cattle arrived. A 1627 division of cattle lists 156 colonists divided into twelve lots of thirteen colonists each.[27] Another ship likewise named the Mayflower arrived in August 1629 with 35 additional members of the Leiden congregation. Ships arrived throughout the period between 1629 and 1630 carrying new settlers; though the verbal number is unknown, contemporary documents claimed that by January 1630 the colony had almost 300 people. In 1643 the colony had an estimated 600 males fit for military service, implying a total population of about ii,000. By 1690, on the eve of the dissolution of the colony, the estimated full population of Plymouth County, the most populous, was 3,055 people. Information technology is estimated that the entire population of the colony at the point of its dissolution was around 7,000.[28] For comparing it is estimated that between 1630 and 1640, a flow known equally the Keen Migration, over 20,000 settlers had arrived in Massachusetts Bay Colony solitary, and past 1678 the English language population of all of New England was estimated to be in the range of sixty,000. Despite the fact that Plymouth was the first colony in the region, by the fourth dimension of its absorption information technology was much smaller than Massachusetts Bay Colony.[29]

Based on the early friendship with the Plymouth colonists, for well-nigh 40 years the Wampanoag and the English language Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony maintained an increasingly uneasy peace until Massasoit's death. Growing tensions betwixt English language colonists and Native Americans, who found their lands being lost and traditions beingness eroded, led to the decisive effect of seventeenth-century English language colonial history, the region-wide King Phillips War, 1675 to 1676. The state of war pitted English colonists and their numerous Indian allies confronting militant Indian tribes led past Massasoit'south son, Metacomet, known to the English every bit "King Philip." The war killed about 7 of every eight Indians and was proportionately one of the bloodiest and costliest in the history of America.[30]

The Plymouth colony independent roughly what at present comprises Bristol, Plymouth, and Barnstable counties in Massachusetts. When the Massachusetts Bay Colony was reorganized and issued a new lease every bit the Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1691, Plymouth concluded its history as a separate colony.

The Pilgrims' legacy

The colonists at Jamestown and Plymouth faced similar hardships and demonstrated equal measures of fortitude, yet these primeval English language settlements bequeathed differing legacies that shaped later colonial and U.S. history. In Jamestown, the cultivation of tobacco as the principal cash ingather, the inflow of the first African slaves in 1619, and the emergence of an aristocratic planter class underscored the colony's commercial origins and contrasted with the more egalitarian and religiously devout ethics of the Plymouth colony.

The Mayflower Meaty, signed upon the ship's arrival on New England's shores, established the offset fully representational government in America and upheld the principle of government past law with the consent of the people. The Plymouth community initiated consensus authorities that depended upon word and reason, which was emulated throughout New England through the forum of the boondocks meeting.[31]

The Pilgrims' experience of tolerance and accommodation in Holland would profoundly influence their come across with both Native Americans and dissenters. The colonists' fortuitous meeting with Samoset and Squanto, and their warm relations with the sachem Massasoit, led to a peace treaty with the Wampanoag that would endure for forty years. In contrast to the too-common design of European paternalism and mistreatment of native peoples, the Pilgrims respected the inhabitants who, Edward Winslow wrote, "considered themselves caretakers of this country […] owned by none, only held and used with respect by all."[32]

Different later Puritans, the Pilgrims did not engage in witch hunts or persecute dissenters. Following John Robinson'south cheerio injunction at Delfshaven—that "If God reveal anything to y'all by any other musical instrument of His, be every bit ready to receive information technology as you were to receive any truth from my ministry, for I am verily persuaded the Lord hath more truth and light yet to break forth from His holy word"—Plymouth would stand equally the most liberal and tolerant religious community in the New Globe.[33] William Bradford, like many of the Cambridge-educated separatists who upheld the principle of individual conscience, wrote: "Information technology is too great arrogancy for any man or church building to call back that he or they accept and so sounded the word of God to the bottom as precisely to set down the church'due south discipline without error in substance or circumstance, as that no other without blame may digress or differ anything from the same."[34]Thus the nonconformist Roger Williams could spend more than than ii years at Plymouth as a instructor before returning to neighboring Massachusetts Bay, from whence he was soon exiled for spreading "diverse, new, and dangerous opinions."

The Plymouth colony'southward example of industry, faith in the providential guidance of God, respect for censor, and practice of popular democratic governance would in fourth dimension become defining values of the U.s. and earn the Pilgrim fathers the reverence of afterward generations of Americans. At a ceremony in 1820 on the two-hundredth anniversary of the Pilgrims' landing, the American statesman Daniel Webster said,

We have come up to this Rock to record here our homage for our Pilgrim Fathers; our sympathy in their sufferings; our gratitude for their labours; our adoration of their virtues; our veneration for their piety; and our attachment to those principles of ceremonious and religious freedom, which they encountered the dangers of the ocean, the storms of heaven, the violence of savages, disease, exile, and famine, to enjoy and establish. – And we would leave here, too, for the generations which are ascension upwards rapidly to make full our places, some proof, that we accept endeavored to transmit the bully inheritance unimpaired; that in our estimate of public principles, and private virtue; in our veneration of religion and piety; in our devotion to civil and religious liberty; in our regard to any advances human knowledge, or improves man happiness, we are non birthday unworthy of our origin.[35]

Notes

- ↑ Samuel Eliot Morrison, The Oxford History of the American People (New York: Oxford University Press, 1965) 55

- ↑ Alden T. Vaughn. New England Frontier: Puritans and Indians 1620-1675. (New York: W.Westward. Norton, 1979 ISBN 0393009505), 65

- ↑ Cornelius Chocolate-brown, "Scrooby" A History of Nottinghamshire. (London: Elliot Stock, 1896). [one] Nottshistory.org.u.k.. Retrieved June 18, 2007.

- ↑ [ii] The Bawdy Court: Exhibits - Belief and Persecution. Academy of Nottingham. accessdate June eighteen, 2007

- ↑ William Joseph Sheils, "Matthew, Tobie (1544?–1628)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (Oxford University Printing, 2004)

- ↑ Brown, 1896, A history of Nottinghamshire. accessdate June 18, 2007

- ↑ Bradford, William, 1698 Of Plymouth Plantation. [3]Bradford'south History of Plymouth Plantation. (with English linguistic communication updated) Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- ↑ Bradford, History

- ↑ "Contract of Sale, De Groene Poort" [4]. Leiden Pilgrim Archives. accessdate June 18, 2007

- ↑ William Elliot Griffis, "The Pilgrim Press in Leyden" New England Magazine 19 (25)(January 1899): 559-575 [5] Cornell Univ. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- ↑ Bradford, History, chapter 4

- ↑ Edward Winslow, "Hypocricie Unmasked," 2nd department, [6] Caleb Johnson accessdate June eighteen, 2007

- ↑ The records of the Virginia Company of London: The Courtroom Volume, vol. I. editor Susan Myra Kingsbury, 1908. (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Press Part), 228

- ↑ Bradford,History, chapter 5

- ↑ Bradford, History, chapter 6.

- ↑ The Charter of New England: 1620 The Avalon Projection at Yale Police force School. accessdate June 18, 2007

- ↑ Griffis, 559-575

- ↑ Bradford, History, chapter 7

- ↑ Bradford, History, chapter 8-ix

- ↑ Edward Winslow, and William Bradford, [seven] "Mourt's Relation" Plymouth Colony. accessdate June xviii, 2007

- ↑ Mayflower Compact, 1620, [8] Plymouth Colony Archive Project. accessdate June 18, 2007

- ↑ Bradford, History, Volume two

- ↑ Smith'due south Map of New England, 1614. The Plymouth Colony Archive Project. accessdate 2006-06-02

- ↑ Jerry Wilson. "The Thanksgiving Story." Holiday Page, Wilstar.com 2001 [9]. accessdate 2007-04-05

- ↑ Winslow

- ↑ Nathaniel Philbrick. Mayflower: A Story of Backbone, Community, and War. (Penguin, 2006), 123–126, 134

- ↑ "Residents of Plymouth according to the 1627 Division of Cattle" Plimoth Plantation: Living, Breathing History. [ten]. Plimoth Plantation. accessdate 2007-05-02

- ↑ Douglas Edward Leach, "The Military Organization of Plymouth Colony" The New England Quarterly 24 (3)(Sep., 1951): 342–364 doi = x.2307/361908 [eleven] accessdate 2007-04-03 (annotation: login required for admission)

- ↑ Norris Taylor website, "The Massachusetts Bay Colony." = 1998 [12]. accessdate 2007-03-30

- ↑ Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias. Male monarch Philip'due south War: The History and Legacy of America'due south Forgotten Conflict. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2000. ISBN 0881504831

- ↑ Robert Merrill Bartlett, Memorial Address, 1966 entitled "Our Pilgrim Heritage." [13] Sail 1620. retrieved Feb 28, 2008

- ↑ Jeremy Dupertuis Bangs, "1621: A Historian Looks Anew at Thanksgiving," from Butterflies and Wheels[14] Retrieved February 28, 2008

- ↑ Bartlett[15]

- ↑ Bartlett [16]

- ↑ Daniel Webster, "Plymouth Oration," December 22 1820 [17] Retrieved February 28, 2008

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bradford, William 1698 Of Plymouth Plantation. [xviii]Bradford's History of Plymouth Plantation. (with English linguistic communication updated) Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- Bremer, Francis J. The Puritan Experiment New England Society from Bradford to Edwards, (original 1976) Revised Ed. University Press of New England, 1995. ISBN 0874517281

- Dark-brown, Cornelius, "Scrooby" A History of Nottinghamshire. (London: Elliot Stock, 1896). online [nineteen] Nottshistory.org.uk. Retrieved June 18, 2007

- Leach, Douglas Edward, "The Military machine System of Plymouth Colony." The New England Quarterly 24 (3)(Sep. 1951): 342–364

- Morrison, Samuel Eliot. The Oxford History of the American People. New York: Oxford University Press, 1965.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War. Penguin, 2006. ISBN 0143111973

- Plymouth Plantation. Mourt'south Relation, published in cooperation with Plimoth Plantation by Applewood Books, Bedford MA, Edited past Dwight B. Heath (from the original text of 1622), copyright 1963 past Dwight B. Heath, ISBN: 0918222842.

- Schultz, Eric B. and Michael J. Tougias. Male monarch Philip's War: The History and Legacy of America's Forgotten Conflict. New York: West.W. Norton and Co., 2000. ISBN 0881504831

- Vaughn. Alden T. New England Borderland: Puritans and Indians 1620-1675. New York: Westward.W. Norton, 1979. ISBN 0393009505

External links

All links retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Church of the Pilgrimage, Plymouth, Massachusetts

Credits

New Globe Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia commodity in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa three.0 License (CC-past-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click hither for a listing of adequate citing formats.The history of earlier contributions past wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Pilgrim_Fathers history

- Massasoit history

- Plymouth_Colony history

The history of this commodity since it was imported to New Earth Encyclopedia:

- History of "Pilgrim Fathers"

Note: Some restrictions may employ to utilise of individual images which are separately licensed.

Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Pilgrim_Fathers

0 Response to "What Was Family Life Like for the Pilgrims"

Post a Comment